Patricia Kuhl 談嬰兒的語言天分

Patricia Kuhl :嬰兒的語言天分

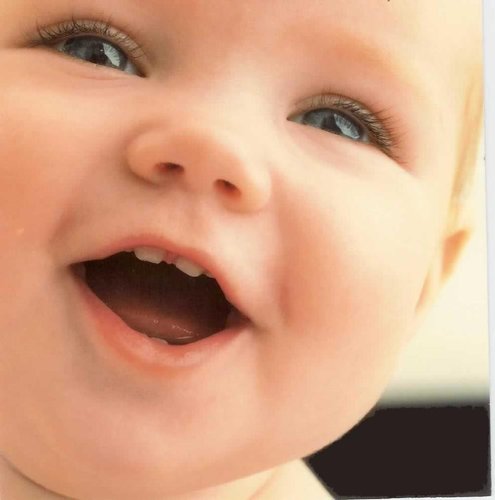

請大家看一看這個小嬰兒,你會被她的眼睛所吸引,也會想摸摸她粉嫩的肌膚,但是今天我要跟大家談談你所看不到的東西,在她的小腦袋裡發生的事情。現代的神經科學儀器向我們顯示,腦袋瓜裡發生的是極度高深的事,我們研究的結果將會向我們揭示浪漫作家和詩人所描述的,小孩有如「天空般開放」的心靈。

我們在這裡看到的是一位在印度的母親,她說的是一種叫做Koro的新發現語言,她正在跟她的寶寶講話,這個媽媽和全世界共800個講Koro語的人都很清楚,想保存這個語言就必須跟新生兒說這個語言,這裡面有個關鍵的謎題:為什麼跟你我這樣的成年人說是無法保存這個語言的呢?嗯,這跟你我的大腦有關。我們知道的是,學習語言有一段關鍵時期,讀懂這張投影片的方法是看水平軸上你的年齡。(笑聲)你可以看到,垂直軸是你學習第二外語的能力,嬰兒和幼童在七歲前都是學習語言的天才,之後這個能力就會逐漸遞減,青春期後曲線就掉到圖外了。所有科學家都認同這條曲線,但全世界各大實驗室都試圖找出產生這種情形的原因。

我實驗室的研究著眼於發展過程中第一個關鍵時期,也就是嬰兒試著掌握使用在語言中的語音時期。我們認為,藉由研究語音是如何被學習的,就能建立起學習其他語言的模式,也許還能找出可能存在於幼童期發展出社交能力、情緒、認知能力的關鍵時期,所以我們研究嬰兒,用了一個我們用於世界各地和所有語言中語音上的技巧,我們把嬰兒放在父母大腿上,訓練嬰兒聽到語音改變時轉頭,像從「ah」變成「ee」時,如果他們在對的時間轉頭,這個黑盒子就會亮起來,熊貓也會開始敲鼓,六個月大的嬰兒很喜歡這個遊戲。

我們從中瞭解到什麼?世界上所有的嬰兒,我喜歡稱呼他們為世界公民,都能分辨所有語言中的所有語音,不論我們在哪一國用哪一種語言測試。這很了不起,因為你我都辦不到。我們是受到文化束縛的聆聽者,我們能分辨我們自己語言裡的語音,無法分辨外國語言裡的語音,所以問題來了,這些世界公民是什麼時候變成像我們一樣受文化束縛的聆聽者?答案是:一歲以前。你在這裡看到的是對東京和美國嬰兒進行的轉頭測試,這是在西雅圖做的,他們分別聽「ra」和「la」,在英語中很重要的語音,但日語中不是,六到八個月的嬰兒表現完全一樣。兩個月後,不可思議的事發生了。美國的嬰兒分辨得越來越好,日本的嬰兒卻越來越差,這兩組嬰兒正同處於準備學習母語的階段。

所以問題是,在這關鍵的兩個月發生了什麼事?這是語音發展的重要階段,在嬰兒腦袋裡發生了什麼事?有兩件事發生了:第一,嬰兒一直專心聽我們的說話,他們一邊聽一邊在腦海裡作統計,他們在做統計,聽兩個媽媽說的「媽媽語」,也就是我們對小孩說話時一般用的語言,先是英語,再來是日語。

(影片)美國媽媽:啊,我好喜歡你的藍色大眼睛,好漂亮,好美喔!

日本媽媽:[日語]

Patricia Kuhl :在語言產生的階段,當嬰兒聆聽的時候,他們是在做統計,統計他們聽到的語音,語音的分佈情況也會改變,我們得知的是,嬰兒們對語音統計很敏感,英語和日語的語音統計十分不同,英語有很多的「R」和「L」,從這個分佈可以看出,日語的語音分佈是完全不同的,我們可以看到有一群分佈於其間的語音,就是所謂日語的R,嬰兒會吸收語言的統計分佈,進而改變他們的大腦,這使他們從世界公民變成跟我們一樣受文化限制的聆聽者。但我們成年人不再會吸收這些統計結果,我們受制於早期發展時形成的記憶。

所以我們這裡看到的是,這個關鍵時期如何改變我們的語言模式,我們從數學的觀點來看,語言資訊的學習在分佈穩定後就會慢下來,對會雙語的人來說,這引發很多疑問。會雙語的人必須同時記住兩套統計資料,並隨著談話對象在兩者間切換。

所以我們自問,嬰兒可以對全新的語言作統計嗎?我們測試了這個,讓處在發展關鍵時期,從未聽過第二種語言的美國嬰兒第一次聽中文。我們已經知道,用中文語音測試在臺北或西雅圖的單語嬰兒,他們顯示相同的模式,六到八個月大的嬰兒完全一樣。兩個月以後,不可思議的事發生了,臺灣的嬰兒變得更好,美國嬰兒則不是。我們接下來讓這個關鍵期的美國嬰兒聽中文,就像有個說中文的親戚來拜訪一個月,住在你家裡,並讓嬰兒上了12堂中文課,這是一段在實驗室的影片。

(影片)中文:發生了什麼事情呢?小小熊七七在這裡,一個綠色的圈圈,綠色的圈圈,綠色的圈圈,轉一下,轉一圈!嘿,一圈,再一次喔!轉一,一,二,三。

PK:所以,我們對這些小腦袋做了什麼?(笑聲)我們必須進行一個控制組,來證明光進一趟實驗室是無法增進你中文能力的,所以有一組嬰兒來實驗室聽英語,我們可以從圖上看到,接觸英語並不能增進他們的中文能力,但看看聽了12堂中文課的嬰兒有什麼改變?他們的中文就跟住在臺灣聽了十個半月中文的嬰兒一樣好,這證明了嬰兒能對新的語言做統計,不論你讓他們聽什麼語言,他們都會做統計。

我們也想知道人類在這個學習裡面扮演著什麼角色,所以我們又測試了另一組嬰兒,他們也聽了12堂中文課,但是是透過電視(視覺組),另外有一組嬰兒是在螢幕上只有泰迪熊的電視聽中文(聽覺組)。我們對他們的腦袋做什麼了?這裡看到的是聽覺組的結果,完全沒學到什麼,這是視覺組的結果,也沒有學到東西,所以嬰兒只會對真人的聲音作統計。嬰兒作語音統計時是由掌管社交的大腦來控制。

我們想進入大腦裡,看看嬰兒在電視和真人前,大腦發生什麼不同情況。幸運的是,我們有個新機器,腦磁圖監測儀能幫我們做到這一點。這看起來像火星來的吹風機,但完全安全,完全非侵入性,而且是靜音的,空間上的觀測精確度達毫米,並有達毫秒的時間精確度,使用了306個SQUIDs,這些是超導量子干涉元件,可以偵測我們思考時大腦磁場的改變,我們是全世界第一個用腦磁儀記錄嬰兒學習時腦波的變化。

這是小Emma,她六個月大,她正用耳裡的耳機聽不同的語言。你可以看到,她可以自由轉動,我們用頭盔裡的小球來追蹤她的頭,所以她可以完全不受限制的自由轉動。這是科技的精心傑作,我們在看什麼?我們在看嬰兒的大腦,當嬰兒聽到她母語裡的字時,聽覺區會亮起來,接著四周鄰近區域也會亮起來。我們認為這和一致性有關,使大腦與不同區域同步,並且有因果關係,大腦區域引起其他區域的活化。

我們開啟了一個關於嬰兒大腦發展知識的偉大黃金時期,我們將能觀察幼童的大腦,當他們產生情緒、學習說話和閱讀,當他們解決數學問題,或興起一個念頭時,我們也將能發明針對腦部的治療,來醫治有學習障礙的小孩,就像詩人和作家描寫的一樣,我想,我們將能夠看到那不可思議開放的、全然而完整開放的孩童心靈。在研究孩童大腦的同時,我們也將能解開,這對人類來說意味著什麼這個深奧的事實,在這個過程中,我們也能使我們心靈保持在終身學習的狀態。

謝謝大家。

(掌聲)

About this talk

At TEDxRainier, Patricia Kuhl shares astonishing

findings about how babies learn one language over another -- by listening to

the humans around them and "taking statistics" on the sounds they

need to know. Clever lab experiments (and brain scans) show how 6-month-old

babies use sophisticated reasoning to understand their world.

About Patricia Kuhl

Patricia Kuhl studies how we learn language as babies,

looking at the ways our brains form around language acquisition. Full bio and

more links

Transcript

I want you to take a look at this baby. What you're

drawn to are her eyes and the skin you love to touch. But today I'm going to

talk to you about something you can't see, what's going on up in that little

brain of hers. The modern tools of neuroscience are demonstrating to us that

what's going on up there is nothing short of rocket science. And what we're

learning is going to shed some light on what the romantic writers and poets

described as the "celestial openness" of the child's mind.

What we see here is a mother in India, and she's

speaking Koro, which is a newly-discovered language. And she's talking to her

baby. What this mother -- and the 800 people who speak Koro in the world --

understand that, to preserve this language, they need to speak it to the

babies. And therein lies a critical puzzle. Why is it that you can't preserve a

language by speaking to you and I, to the adults? Well, it's got to do with

your brain. What we see here is that language has a critical period for learning.

The way to read this slide is to look at your age on the horizontal axis.

(Laughter) And you'll see on the vertical your skill at acquiring a second

language. Babies and children are geniuses until they turn seven, and then

there's a systematic decline. After puberty, we fall off the map. No scientists

dispute this curve, but laboratories all over the world are trying to figure

out why it works this way.

Work in my lab is focused on the first critical period

in development -- and that is the period in which babies try to master which

sounds are used in their language. We think by studying how the sounds are

learned, we'll have a model for the rest of language, and perhaps for critical

periods that may exist in childhood for social, emotional and cognitive

development. So we've been studying the babies using a technique that we're

using all over the world and the sounds of all languages. The baby sits on a

parent's lap, and we train them to turn their heads when a sound changes --

like from "ah" to "ee". If they do so at the appropriate

time, the black box lights up and a panda bear pounds a drum. A six-monther

adores the task.

What have we learned? Well, babies all over the world

are what I like to describe as citizens of the world; they can discriminate all

the sounds of all languages, no matter what country we're testing and what

language we're using. And that's remarkable because you and I can't do that.

We're culture-bound listeners. We can discriminate the sounds of our own

language, but not those of foreign languages. So the question arises, when do

those citizens of the world turn into the language-bound listeners that we are?

And the answer: before their first birthdays. What you see here is performance

on that head turn task for babies tested in Tokyo and the United States, here

in Seattle, as they listened to "ra" and "la" -- sounds

important to English, but not to Japanese. So at six to eight months the babies

are totally equivalent. Two months later something incredible occurs. The

babies in the United States are getting a lot better, babies in Japan are

getting a lot worse, but both of those groups of babies are preparing for

exactly the language that they are going to learn.

So the question is, what's happening during this

critical two-month period? This is the critical period for sound development,

but what's going on up there? So there are two things going on. The first is

that the babies are listening intently to us, and they're taking statistics as

they listen to us talk -- they're taking statistics. So listen to two mothers

speaking motherese -- the universal language we use when we talk to kids --

first in English and then in Japanese.

(Video) English Mother: Ah, I love your big blue eyes

-- so pretty and nice.

Japanese Mother: [Japanese]

Patricia Kuhl: During the production of speech, when

babies listen, what they're doing is taking statistics on the language that

they hear. And those distributions grow. And what we've learned is that babies

are sensitive to the statistics, and the statistics of Japanese and English are

very, very different. English has a lot of R's and L's the distribution shows.

And the distribution of Japanese is totally different, where we see a group of

intermediate sounds, which is known as the Japanese R. So babies absorb the

statistics of the language and it changes their brains; it changes them from

the citizens of the world to the culture-bound listeners that we are. But we as

adults are no longer absorbing those statistics. We're governed by the

representations in memory that were formed early in development.

So what we're seeing here is changing our models of

what the critical period is about. We're arguing from a mathematical standpoint

that the learning of language material may slow down when our distributions

stabilize. It's raising lots of questions about bilingual people. Bilinguals

must keep two sets of statistics in mind at once and flip between them, one

after the other, depending on who they're speaking to.

So we asked ourselves, can the babies take statistics

on a brand new language? And we tested this by exposing American babies who'd

never heard a second language to Mandarin for the first time during the

critical period. We knew that, when monolinguals were tested in Taipei and

Seattle on the Mandarin sounds, they showed the same pattern. 6-8 months,

they're totally equivalent. Two months later, something incredible happens. But

the Taiwanese babies are getting better, not the American babies. What we did

was expose American babies during this period to Mandarin. It was like having

Mandarin relatives come and visit for a month and move into your house and talk

to the babies for 12 sessions. Here's what it looked like in the laboratory.

(Video) Mandarin Speaker: [Mandarin]

PK: So what have we done to their little brains?

(Laughter) We had to run a control group to make sure that just coming into the

laboratory didn't improve your Mandarin skills. So a group of babies came in

and listened to English. And we can see from the graph that exposure to English

didn't improve their Mandarin. But Look at what happened to the babies exposed

to Mandarin for 12 sessions. They were as good as the babies in Taiwan who'd

been listening for 10 and a half months. What it demonstrated is that babies

take statistics on a new language. Whatever you put in front of them, they'll

take statistics on.

But we wondered what role the human being played in

this learning exercise. So we ran another group of babies in which the kids got

the same dosage, the same 12 sessions, but over a television set and another

group of babies who had just audio exposure and looked at a teddy bear on the

screen. What did we do to their brains? What you see here is the audio result

-- no learning whatsoever -- and the video result -- no learning whatsoever. It

takes a human being for babies to take their statistics. The social brain is

controlling when the babies are taking their statistics.

We want to get inside the brain and see this thing

happening as babies are in front of televisions, as opposed to in front of

human beings. Thankfully, we have a new machine, magnetoencephalography, that

allows us to do this. It looks like a hair dryer from Mars. But it's completely

safe, completely non-invasive and silent. We're looking at millimeter accuracy

with regard to spacial and millisecond accuracy using 306 SQUIDs -- these are

superconducting quantum interference devices -- to pick up the magnetic fields

that change as we do our thinking. We're the first in the world to record babies

in an MEG machine while they are learning.

So this is little Emma. She's a six-monther. And she's

listening to various languages in the earphones that are in her ears. You can

see, she can move around. We're tracking her head with little pellets in a cap,

so she's free to move completely unconstrained. It's a technical tour de force.

What are we seeing? We're seeing the baby brain. As the baby hears a word in

her language the auditory areas light up, and then subsequently areas

surrounding it that we think are related to coherence, getting the brain

coordinated with its different areas, and causality, one brain area causing

another to activate.

We are embarking on a grand and golden age of knowledge

about child's brain development. We're going to be able to see a child's brain

as they experience an emotion, as they learn to speak and read, as they solve a

math problem, as they have an idea. And we're going to be able to invent

brain-based interventions for children who have difficulty learning. Just as

the poets and writers described, we're going to be able to see, I think, that

wondrous openness, utter and complete openness, of the mind of a child. In

investigating the child's brain, we're going to uncover deep truths about what

it means to be human, and in the process, we may be able to help keep our own

minds open to learning for our entire lives.

Thank you.

(Applause)

留言列表

留言列表